Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression

902 T Street NW: Former home of the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression

A rarity at the time of its founding in 1903, the Washington Conservatory of Music was a privately owned, Black founded, and Black run arts institution, specifically created for Black adults and children. The Conservatory educated students about African American musical heritage, and also trained them to play, producing top musicians for decades, until closing in 1960.

Black residents in post-civil war DC set out to cultivate their own musical, economic, and educational institutions due to being locked out of the city’s established all-white institutions. The Conservatory is a crucial part of that story and was a major contributor to the “Black Broadway” era of DC history, centered on nearby U Street NW.

Mary Church Terrell’s remarks at the dedication of the Conservatory | Library of Congress

Harriet Gibbs | Oberlin College Archives.

The founder of the Washington Conservatory was Harriet Gibbs. Born in Vancouver, British Columbia to American parents but educated in Ohio including at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, Gibbs landed in the District of Columbia by 1900. By the time she arrived, she had already traveled the world while studying and performing, and was considered an accomplished pianist with over a decade of experience as a music educator.

Gibbs initially ran the Washington Conservatory of Music from studios inside True Reformer Hall at 1200 U Street NW, just blocks away. By 1904, the institution grew and moved into 902 T Street NW, a stunning and beautiful building donated to the Conservatory by Gibbs’ father.

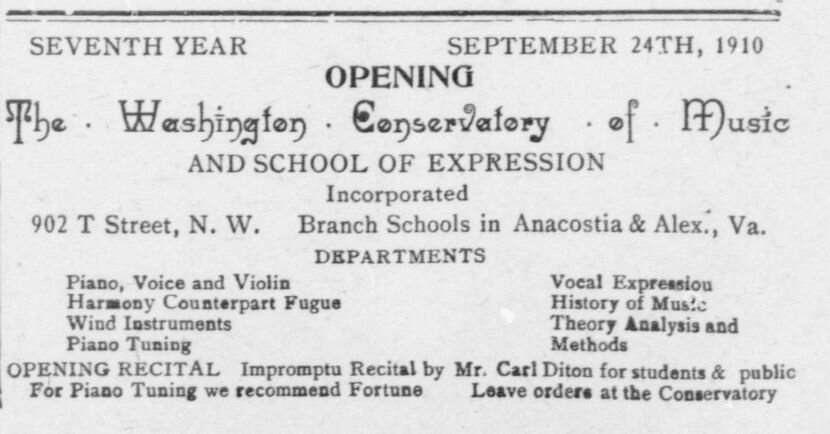

In addition to musical history, with an emphasis on Black musical history, students at the Conservatory received instruction in strings, piano, voice, pipe organ, and wind instruments, among others. Instruction was a true combination of both Western/European music traditions and African American musical traditions. After a new program was added for rhetorical skills and public speaking, the name of the institution was changed to the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression.

The Conservatory helped consolidate funding for the concert music scene for Black artists in Washington. Previously performances, training, and schooling were sponsored by various institutions including Black churches as well as Howard University.

Advertisement in the Washington Bee, 1910 | Library of Congress.

In the Conservatory’s first years, Gibbs and the other founding faculty tried to strike a balance between student recitals and hosting better known, traveling artists and orators, all while maintaining financial stability as a privately run school. The faculty worked as tirelessly as Gibbs herself.

Early faculty member Emma Azalia Hackley made the long commute from Philadelphia to teach for a full academic year; an assignment she considered a privilege. At the pinnacle of its existence, the Conservatory would host up to 175 students with fourteen faculty members operating out of the T Street building.

One of the early directors of the Conservatory was Mary (aka Mamie) Burrill.

In 1906, Harriet Gibbs married Napoleon Bonaparte Marshall, a famed Harvard graduate, lawyer, and eventual World War I veteran and diplomat. They moved to New York City soon after. Post war, the Marshalls moved to Haiti (1922-1928) when Napoleon received assignment from President Harding. Ever the educator, Harriet Gibbs Marshall founded a school in Port-au-Prince and in 1930, and even authored a book on the history of Haiti, titled The Story of Haiti. She returned her full focus to the Washington Conservatory of Music after her husband’s death n 1933.

In Gibbs Marshall’s absence Burrill, another lifelong educator, ran the school from 1907 through 1911. The first commencement of the Conservatory happened under her tenure in 1910. The ceremony was held at Metropolitan A.M.E. church to an audience of nearly 2,000 people. After serving at the Conservatory, Burrill was likely best known for being a playwright. In 1919, They That Sit in Darkness was first published, landing in Margaret Sanger's Birth Control Review. The one act play is considered to be one of the earliest explicitly feminist plays by a Black playwright. The Conservatory’s success was largely due to the undeniable attraction of talented artists from around the nation, not just as students, but faculty and administration.

I am planning another separate post on Mary Burrill (left) and her partner Lucy Diggs Slowe. Pictured here at their home in Brookland, DC

Capt. Napoleon Bonaparte Marshall. Lawyer, war veteran, athlete, diplomat, and husband of Harriet Gibbs | The American Negro in the World War

In 1941 Gibbs, then known as Harriet Gibbs Marshall, died aged 73 years. While the Conservatory continued under the leadership of her cousin, Josephine Muse, it ultimately closed in 1960 after Muse passed away. The Conservatory’s records and materials live on at Howard University’s Moorland-Springarn Research Center. Both Harriet and Napoleon were laid to rest just a few miles from the old Conservatory at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 4.

The Washington Conservatory of Music and School Expression is not to be confused with the modern (c. 1984) non-profit organization Washington Conservatory of Music located in Bethesda, MD

For more weekly DC history posts, photos, inside access to tour development, and more, support us on Patreon. Plans start at just $3/mo.

Advertisement listed in The Crisis, May 1913

902 T Street NW, former home of the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression.

Read more:

The Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression | JSTOR

Cultivating Music in America: Women Patrons and Activists | Univ. of California Press

Harriette Gibbs Marshall | Oberlin College Library

Washington Conservatory of Music | Howard Moorland-Spingarn Research Center

Burrill, Mary P. ( Mamie Burrill) | Oxford African American Studies Center

A reading of Burrill's They That Sit in Darkness. | Triad Stage (Wilmington, NC).

9th Street NW

True Reformers: From Alabama to U Street

Even before Industrial Bank or Southern Aid Society provided capital, financial services, and insurance plans for Black businesses on U Street, a fraternal organization by the name of True Reformers arrived from Richmond, Virginia to help lay the foundation of what would become Black Broadway.

By the time this building at 1200 U Street NW was dedicated in 1903, the Grand Fountain of the United Order of True Reformers was already one of the most successful Black owned enterprises in the United States.

The origins of the Three Reformers date back to temperance and William Washington Browne. Browne born as an enslaved person in Georgia. During the Civil War, he fought for the Union and after the war became a teacher. He grew to believe that alcohol was the great hindrance to Black wealth and vitality. Not surprisingly, even temperance organizations were segregated. Browne attempted to join the all white Alabama temperance society, Good Templars in 1874. They refused, but helped Browne charter Black chapters across the state under the name Grand Fountain. Browne became the leader of Grand Fountain and grew the chapters throughout and then beyond Alabama, fairly quickly.

Browne was invited to start a similar group in Richmond, Virginia in 1876. There, the mission evolved and expanded. By 1880, the Reformers group in Richmond had become much more than a temperance society. It had evolved into a self-help and mutual benefit organization with the goal of enabling Black members to live without help from the White community. That meant creating Black-focused services such as banking, insurance, and others restricted, segregated industries.

The Savings Bank of the Grand Fountain of the United Order of True Reformers opened in 1888 and was the first Black owned and Black operated financial institution to be chartered in the nation. It was so successful that during the Panic of 1893, they were the only Richmond bank that continued to honor checks. From there, Grand Fountain expanded their financial services offerings over the next quarter century to become arguably the most influential institution for Black commerce nationwide. Browne passed away of cancer in 1897, but by then the True Reformers was a self-sustaining organization with membership in the thousands.

In 1903 the True Reformers’ newly opened structure in Washington at 1200 U Street NW was America’s first to be solely owned by, financed by, designed by, and constructed by African Americans since Reconstruction. They offered a multitude of amenities and services to Black people in DC. Conference rooms, leased office space, a performance hall, and street level retail were all part of the vast offerings beyond financial services.

One of the first businesses to lease space on the ground level was Fountain Pharmacy, opening in 1905. For 12 years, the Fountain was operated by Dr. Amanda Gray who started her own business after graduating from Howard University and working as a pharmacist at the Woman’s Clinic, a care facility located, at the time, near 13th and T Streets NW.

Dr. Gray is thought to have been the first Black woman to own and operate a pharmacy in the city. Her store in the True Reformer building offered additional services such as laundry, mail, and even housed a telegraph office. Dr. Gray also produced a directory of emergency medical services in the city. Dr. Gray ran the Fountain Pharmacy until the death of her husband and fellow pharmacist Arthur in 1917.

During the fledgling first few years of what would become the “Black Broadway” era on U Street, the True Reformer building became known for hosting jazz concerts popular with both youth and adults.

In 1916 a young Duke Ellington played some of his first shows for money inside the rooms of True Reformer Hall, as it was colloquially known, thereby making him a professional musician. Just a year later in 1917, the True Reformers sold the building to the Knights of Pythias, who officially renamed it Pythias Hall, but the old name persists to this day.

Somewhat fittingly, the building is now home to the Public Welfare Foundation, a grant-making organization focused on social justice issues in the United States.

For more weekly DC history posts, photos, inside access to tour development, and more, support us on Patreon. Plans start at just $3/mo.

True Reformer building c. 1990s with its sole tenant, a Duron Paints store. (Library of Congress)

Busy U Street in late 2019.

Read more:

William Washington Browne and the True Reformers of Richmond, Virginia | JSTOR

A Family of Pharmacists | Library of Congress

William Washington Browne | Library of Virginia

Public Welfare Foundation | Public Welfare Foundation

A Story in a Photograph [Patreon Preview]

During these initial few weeks of establishing content on Patreon, we will share a few of the posts usually only available to Patrons. You can support our work and become a Patron here: Attucks Adams on Patreon

Enjoy!

-Tim

Converting a live, in-person walking tour into an online "virtual tour" or "virtual field trip" experience wasn't as straightforward as I initially imagined. The lesson planning, the presentation, even the content have all required drastic change. I've been forced to rethink what themes and important messages I want to get across, and what media I need to illustrate those narratives.

Of course, photographs are key to illustrating an historical narrative, especially when I can't just point to a building and reference history against it in real time. On the flip side, being forced to rethink how I present information has allowed me to even further back up some of the stories I have used on tour with even more nuance.

Looking at the first photograph here: What do you see?

What is the setting? Who are these guests? What are they doing?

As part of the U Street tour (Art & Soul of Black Broadway), I tell a story about Ahmet Ertegun. Ahmet was son of the Turkish Ambassador to the United States. As such, he lived in the Turkish Embassy with his family. Ertegun and his brother Nesuhi were heavy into jazz music and became nuanced fans of the genre. They spent time on 7th Street NW, the "Black Broadway" of Washington, DC at the time, including Howard Theatre and Waxie Maxie's record store.

At the time (early 1940s) Washington, DC was severely segregated like much of the United States, and in most places jazz or any other musical performance would not be played publicly with black and white artists together.

However, the Erteguns had another vision. Ahmet and his brother Nesuhi often hosted salons and jazz concerts with the top artists of their time, specifically inviting Black artists into the embassy, so much so that their neighbors in the all white Sheridan Circle neighborhood questioned why Black folks were allowed to enter the embassy through the front door. Along with the performances and jazz sessions, the Etergun's had all the artists gather over a meal, usually lunch.

This photo is from one of the lunches in the 1940s. Included in the photo are Nesuhi Ertegun, Adele Girard, Joe Marsala, Zutty Singleton, Max Kaminsky, an unnamed person, Ahmet M. Ertegun, Sadi Coylin, and (likely) Benny Morton.

Ahmet Ertegun went on to graduate studies at Georgetown University and while there, started a small record label for DC r&b and gospel artists. He later enlisted an investment and partnership from friend Herb Abramson. By 1947 they had incorporated Atlantic Records in New York City. Atlantic Records became one of the most influential labels in jazz, soul, pop, rock, and other genres.

Most of this information won't make it into the 90 minute tour, but on occasion I have guests who are big on Turkish history, American diplomatic history, long shuttered DC record stores, jazz in America, or any number of tangential topics to the tour. Being able to go just one level deeper into the narrative creates value for guests, and opens a door to further learning for me as the storyteller.

I'll continue to post photos, images, and objects that won't ever make it into a tour, but that drive my research and tour building. I’m grateful for this new outlet!

The photo in this post is from the Library of Congress William P. Gottlieb Collection.